Tour like a pilgrimage for young adult

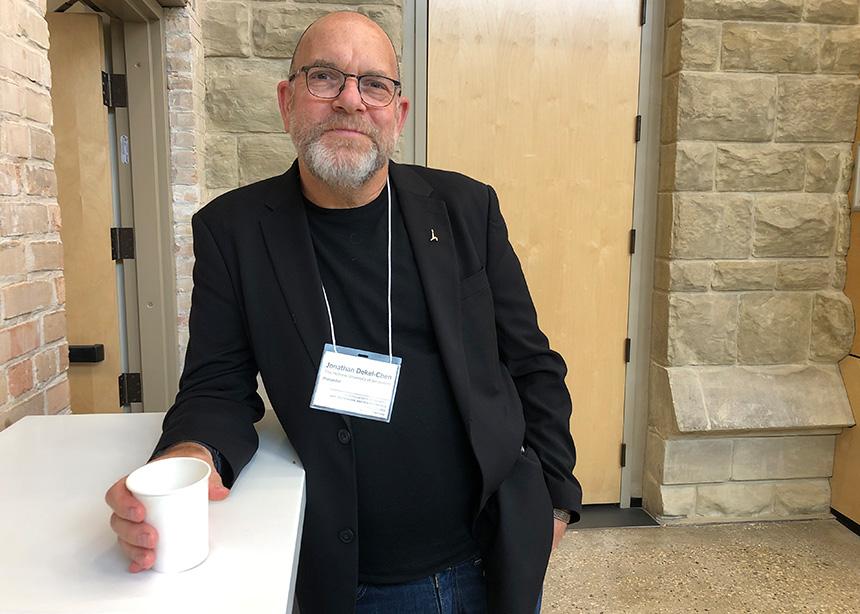

Emily Friesen. (Photo by John Longhurst)

For Emily Friesen, the Memories of Migration: Russlaender 100 Tour was like a pilgrimage.

“As I travelled on the tour, I kept thinking about what it meant for our ancestors to make this journey,” said Friesen, 28, a textile artist from Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

She had read about her great-grandfather’s travels from the Soviet Union to Canada in 1927 before going on the tour.

But actually replicating the journey “helped me learn about it in a way that I hadn’t before,” she said of participating in the second leg as a sponsored young person, travelling from Toronto to Saskatoon.

“My learning was wrapped up in that experience,” she said of the travel by train and the times spent talking with other tour members.

Friesen grew up in Pennsylvania because her grandfather, who was born in Alberta, met her grandmother—who was from that state—at a Bible school in Ontario and then moved there when they married. The tour was a way for her to connect to both her Russlaender and Canadian roots.

As for the idea of pilgrimage and the tour itself, Friesen said she is drawn to the idea of somatic, or experiential knowledge—knowledge that involves the senses.

The tour, she said, was a “sensory experience” as they physically moved from place to place. “It gave me a fuller sense of what their experience was like so long ago,” she noted.

She was especially moved by the auditory experience of the sängerfest in Winnipeg. “Each person there carried so many people from the past in their hearts,” she said of the 2,300 people in the audience plus the 200 or so in the choir. “It was like a cloud of witnesses.”

After she returns home, Friesen thinks she may make some art based on the tour, something that combines the memories of travel, the sharing of stories and the singing.

“It could give me a way to share what I experienced on the tour,” she said.

John Longhurst is a Winnipeg freelance writer who is blogging about the tour.