“The Place of Memory” premieres

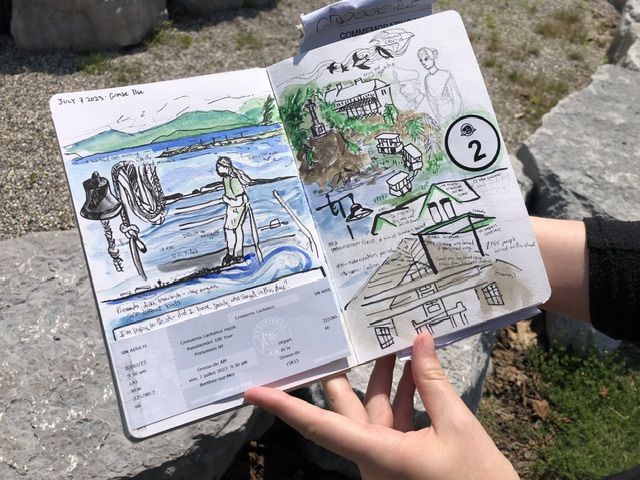

A full house in Waterloo, Ontario for the premiere of ‘The Place of Memory.’(Photos by John Longhurst)

For many Mennonites in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a “promised land,” a “place of memory,” a place where they grew crops, milled grain, raised families and built factories, churches and schools.

That’s how Marlene Epp, professor emeritus of history and peace and conflict studies at Conrad Grebel University College, began her opening remarks on July 10 at Knox Presbyterian Church in Waterloo, Ontario.

She was addressing a full house at “The Place of Memory: Reflections on the Russlaender Centenary,” an evening of music and readings that featured the premiere performance of “The Place of Memory,” composed and conducted by Leonard Enns and performed by the DaCapo choir with cellist Miriam Stewart-Kroeker.

But the place of memory began to change to a place of trauma and horror in 1917 after the Bolshevik revolution for the 100,000 or so Mennonites who lived in 50 settlements in Russia.

That’s when that good and happy life for many began to disappear—they became targets, were “despised” by their neighbours because of their wealth and religion and were subject to attacks.

“There were horrific massacres,” Epp said, along with epidemics such as typhus and starvation.

From a place or memory, it became “a place of tragedy and loss,” she said.

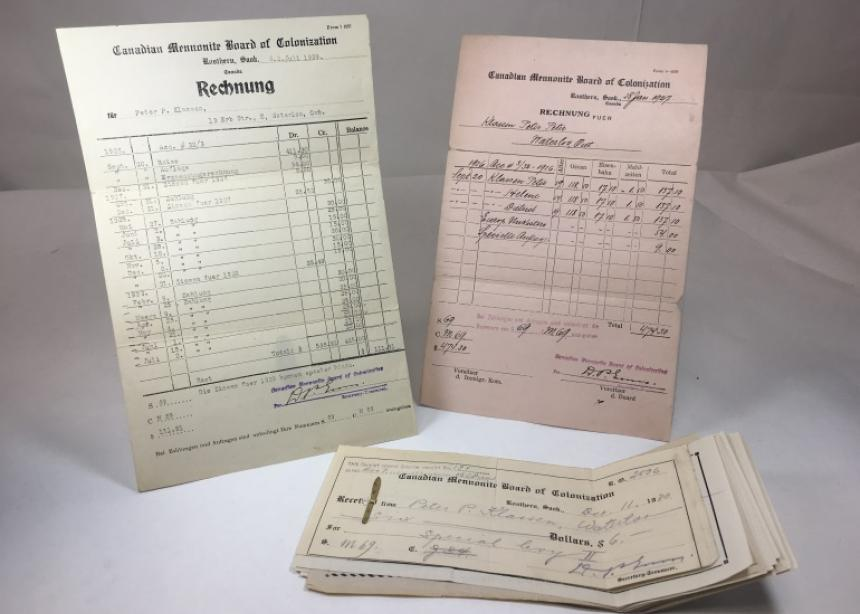

That’s when they began to look for a new home. The U.S. was closed to them, but Canada opened its doors. About 21,000 came between 1923 and 1930 with most, about 15,000, coming from 1924 to 1926.

They came to a new “promised land,” she said, from a “lost paradise.”

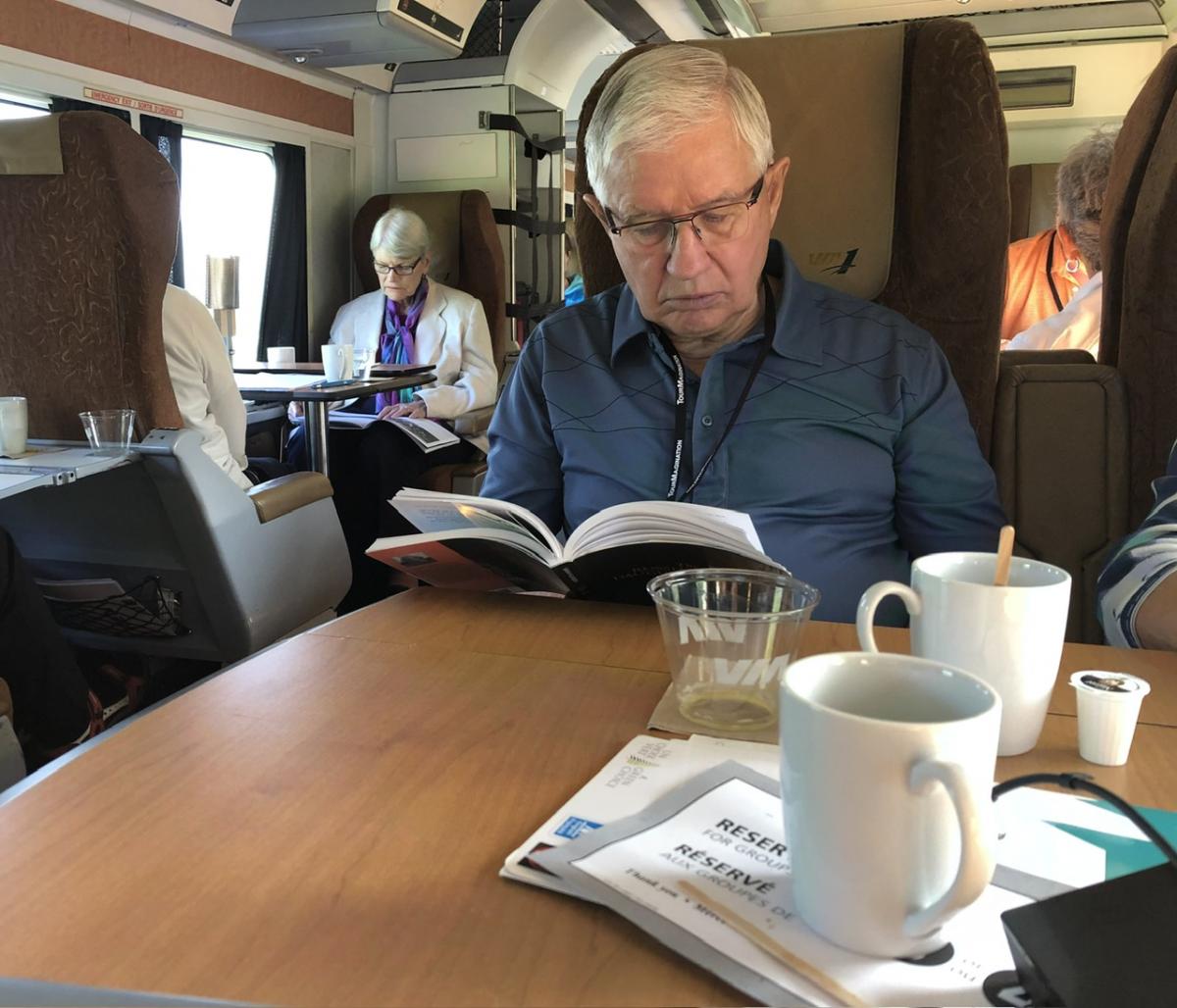

The evening of music and readings was part of “Memories of Migration: Russlaender Tour 100,” which finds participants crossing the country by train to replicate the journey of their ancestors between 1923 and 1930.

In addition to the DaCapo choir’s performance, the congregation sang songs such as Ich weiss einem Strom (Oh, Have You Not Heard), So nimm denn meine Haende (Take Though My Hand) and Wehrlos und verlassen sehnt sich (In the Rifted Rock I’m Resting).

Donations were taken at the event for the Russlaender Remembrance Fund at Mennonite Central Committee.

The fund will support three programs at MCC: MCC’s Indigenous Neighbour’s program, MCC’s work in Ukraine, and its international refugee resettlement program.

For MCC Canada executive director Rick Cober Bauman, the fund is a link between what happened in the past and what is still the reality for too many people today.

“Just as they were welcomed in Canada, MCC will use the fund to welcome and support others who are refugees today, or who have been displaced,” he said. “There is a link between what happened then and what is happening now.”

To make a donation to the fund, go to mcccanada.ca/russlaender-remembrance-fund(link is external).

There are three other public events during the tour: A Sängerfest in Winnipeg this coming Saturday, July 15; a performance of the Mennonite Piano Concerto by Victor Davies at Saskatoon’s Knox United Church on Tuesday, July 18; and another Sängerfest in Abbotsford on Monday, July 24.

John Longhurst is a freelance writer from Winnipeg who is blogging about the tour.